Why I care about community-oriented writing and publishing

My inspiration to help emerging artists succeed traces back to my days as a freelance music photojournalist. From 2003 through 2008 I photographed hundreds of bands, most of them indie artists that often had no record deals or even recorded demos. I was frustrated, because I saw first-hand how many talented artists there were in the Pacific Northwest (where I grew up and lived at the time) yet the mainstream system of music production meant that most of them would never catch a break. The system left them facing challenging odds and it also wasn’t serving people who might enjoy these bands’ music but would never have the opportunity to hear it.

I had dreams of producing live recordings of these bands and making them available to the community. I still do, but my attention has since wandered to writing. While it is unrealistic for all the bands with talent to make it to the national or global stage, I questioned why local stages were limited to small music venues that only a limited few frequented. What about the people who were busy that night, couldn’t afford the cover, lived out of town, or just didn’t like being in sweaty black boxes? If good-quality inexpensive recordings were made available online, it could open up a wider audience and potential revenue for the artists. But who would want to trudge through a list of every wee indie band on Earth playing local gigs? Putting such a collection on shuffle might be fun, but in keeping with the idea of a local stage, I thought focusing on the community where the musicians lived and/or grew up would create a natural local interest. To a large extent, this still should be done, has not been done and I would like to play a part in bringing it into reality.

When I worked at large tech companies on music products, I pitched this idea and while it gained some traction, the conclusion was that since the content was largely unavailable, and even if it was, the location metadata simply did not exist in a usable way, it was not worth pursuing. The tech companies were not about to go out and start recording bands at small venues nor take on the grueling task of sorting out where every artist in their catalog lived. It’s a ton of work and the potential profit is probably lacking, a wise business decision on their parts. That doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be done, if we only did what was profitable, where would culture be?

But my attention strayed, to writing and my own ambitions as a writer. I loved writing and thought I had some good stories to tell (still do), so after several years of freelance journalism and other writing opportunities, I wrote the manuscript for my first novel in 2015. While writing the story, I thought I was an absolute literary genius. I imagined the joy that literary agents would have when they read my first pages. I completed the first draft in six short months, did some minor copyediting and began sending out query letters. The responses were disappointing, no agents bit. Their loss, I figured as I prepared to self-publish the book. Once people got their hands on Electric Love, I was sure that they would… love it.

What I learned through this process of failure was that I had delusions of grandeur and had underestimated the importance of editing and necessity for good marketing — simply putting a book on the shelf does not incline anyone to read it. After time had passed and I re-read the manuscript as well as received feedback from friends and family, I saw that there was much that was lacking and it was far from the work of literary genius I had initially envisaged. More time in the literary world, floating among writing groups and briefly running a bookshop, has revealed to me that I was not the only writer to fall for such delusions.

In 2018, while living in Dumfries, Scotland on a Fulbright at the University of Glasgow, I began to see a path forward, one that brought together my interest in creating a local platform for indie musicians as well as my literary ambitions. As part of Dr. David Borthwick’s MLitt Environment, Culture and Communication course, I took a module on Environment, Technology and Society taught by Dr. Sean Johnston — this module changed everything for me because it was my first encounter with the idea of socio-technical systems, a way of de-centering technology and seeing it as fulfilling a role within existing and ever-changing social systems. Thinking of cultural work, music and literature specifically, within the terms of the socio-technical systems that encompass production, distribution, consumption and so on, the full picture with the various social and technological bits performing their roles opened my eyes to see how changes in technology (low-cost digital on-demand book printing, online booksellers) meant that changes to the present system, or a new system entirely, was possible and might better serve the social and cultural needs of communities. While I had already understood a similar possibility back when I was focused on music, I had not been thinking in terms of socio-technical systems. With publishing, the concept helped me better understand how technical limitations that no longer existed still informed how the socio-technical system of mainstream publishing operated. This is all to say that by looking at the big picture and breaking it into social and technological components, I now could clearly and easily understand possibilities for new ways of sharing cultural work.

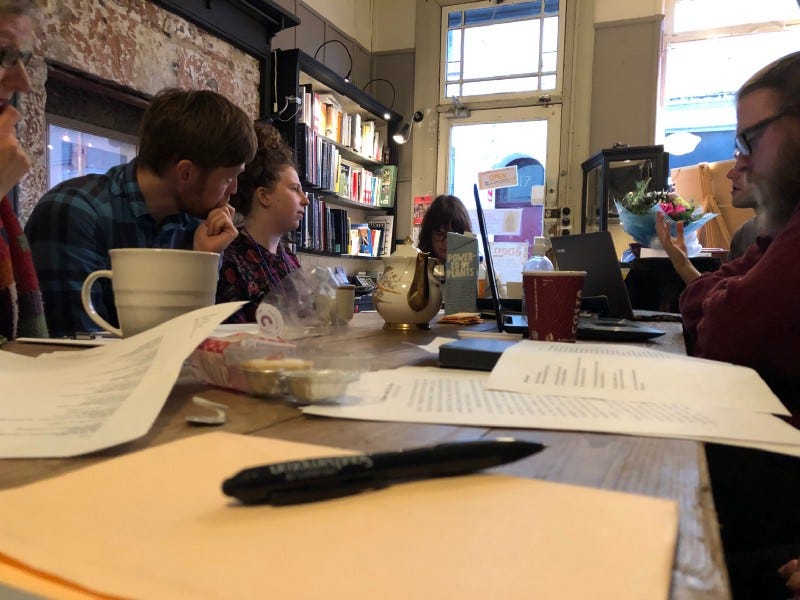

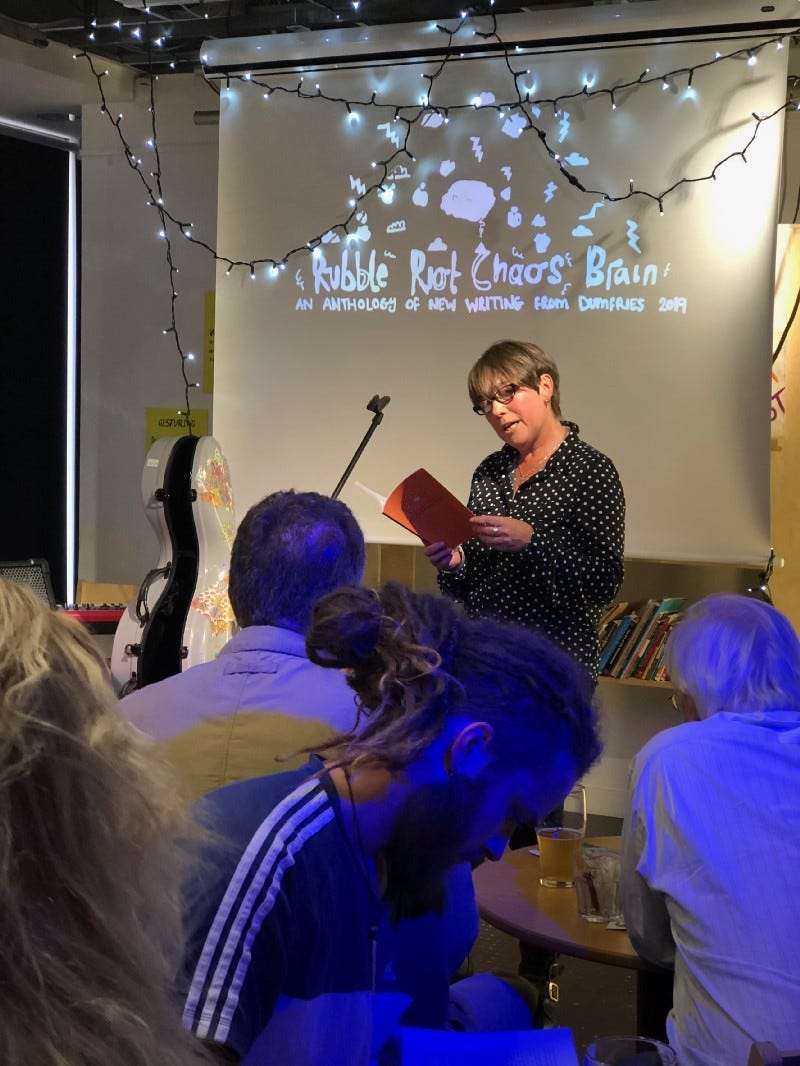

At the time, I was part of a writing group in Dumfries that aspired to publish an anthology of our work. Most participants had never seen their words in print and there was strong interest in moving beyond weekly writing workshops focused on our individual works to actually making something together. In the summer of 2019, we made it happen with Rubble Riot Chaos Brain, a collection of new writing from Dumfries. The project was a great success, garnering strong community interest, from friends and family of contributors but also from community members simply interested in what was going on within their community. If any one of the group members had attempted to release a chapbook of their own work instead of participating in the anthology, it is unlikely they would have seen as much success as the anthology saw. People working together within their community was essential.

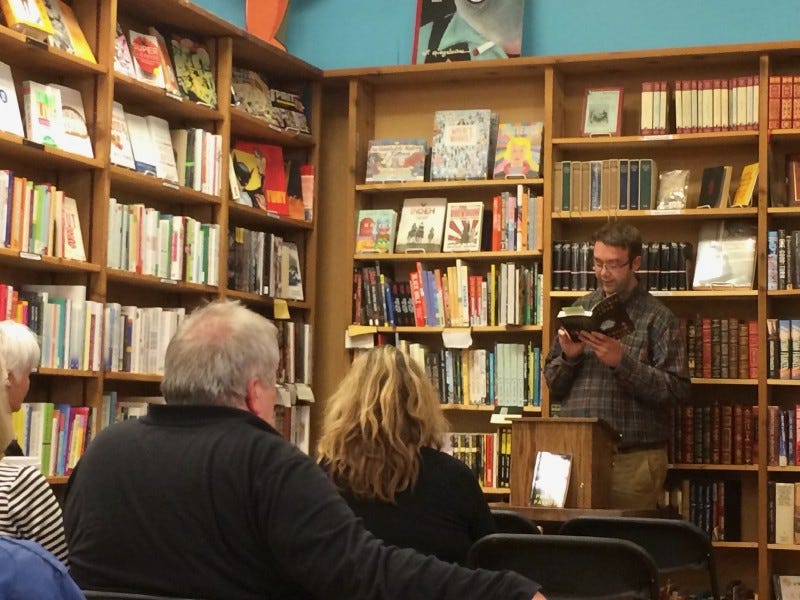

My passion for promoting local literary community inspired me to jump into bookselling with the opening of The Wobbly Shelf in 2021. However, despite all that I did to promote local writers, I found that bigger-name books were far outselling local works. It was a disheartening reality-check. Local writing had potential, but it was not going to replace books being produced by major publishers on most readers’ shelves. The bookshop failed. It had potential as a more traditional independent bookshop, competing directly with the big chains and less focused on local writers. But I would have been bored to tears doing that.

At the time, I had not fully differentiated between the mainstream and community socio-technical systems of publishing. Instead, I was trying to change the former to accommodate the latter rather than seeing them as separate systems entirely. This is one of many things I have learned along the way. Equipped with this new perspective, I have tremendous confidence that building, empowering and connecting writers on a regional basis through a separate socio-technical system of community-focused publishing will serve great social and cultural good. It’s already happening around the world and I’m happy to be a part of it. I will share more specifics on my future plans related to this in an upcoming essay.